To love is to contemplate the icons.

Beware of iconoclasm, for it represents no less than the most perverse revolt against love itself. Pure, distilled odium. A life starved of the possibility to look upon the signs that light the way in the darkness.

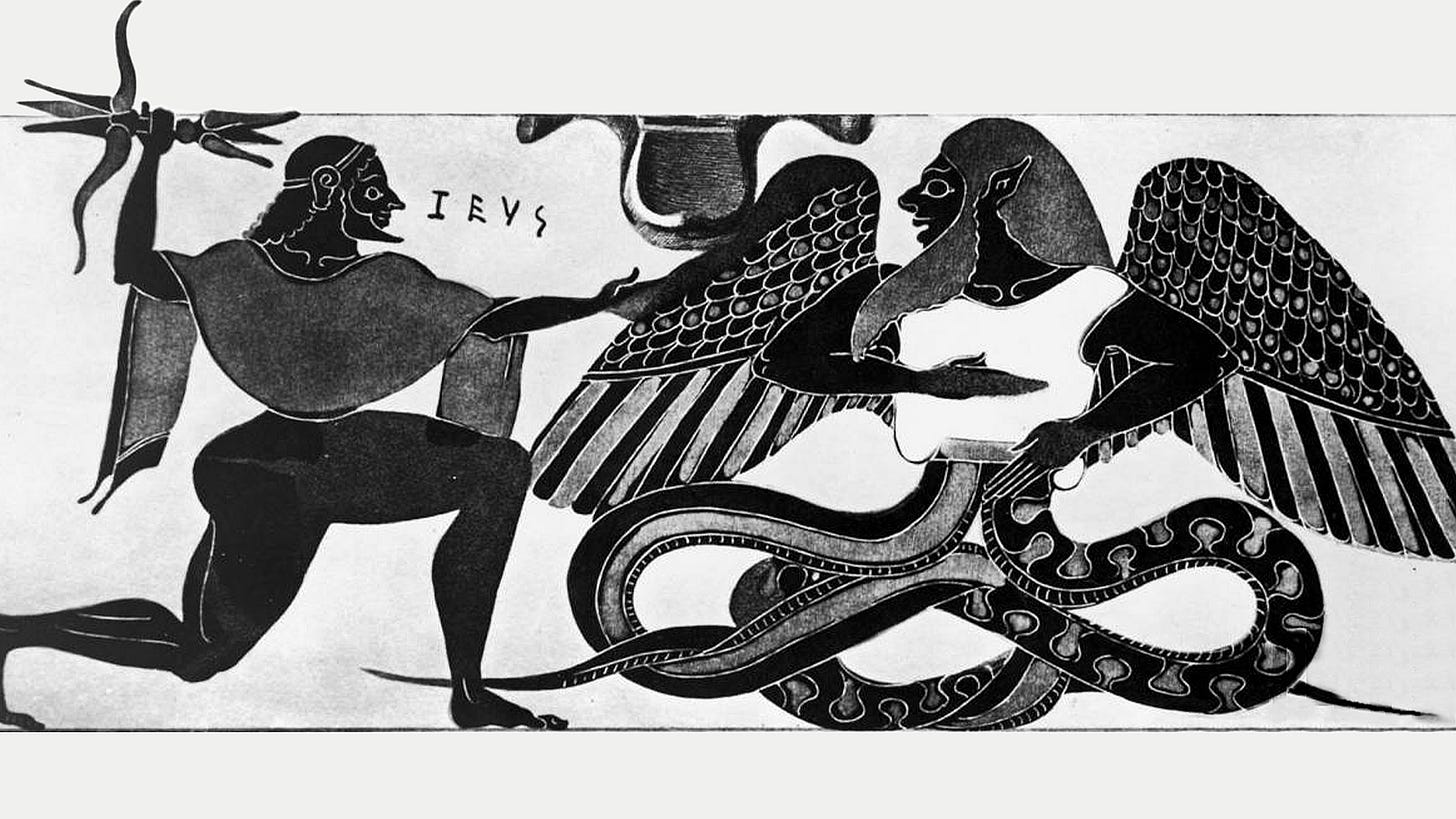

But this most unnatural instinct of revolt against beauty is natural to the world; the world would not be natural without it. In the mythic world, this manifests as hungry monsters that arise to be slain by heroes. In the Theogony (306-332), Hesiod catalogues the offspring of Typhon, father of all obscene freaks of nature, anchoring each to its fate: being felled by a hero.

Men say that Typhaon the terrible, outrageous and lawless, was joined in love to her [Echidna], the maid with glancing eyes. So she conceived and brought forth fierce offspring; first she bare Orthus the hound of Geryones, and then again she bare a second, a monster not to be overcome and that may not be described, Cerberus who eats raw flesh, the brazen-voiced hound of Hades, fifty-headed, relentless and strong. And again she bore a third, the evil-minded Hydra of Lerna, whom the goddess, white-armed Hera nourished, being angry beyond measure with the mighty Heracles. And her Heracles, the son of Zeus, of the house of Amphitryon, together with warlike Iolaus, destroyed with the unpitying sword through the plans of Athene the spoil-driver. She was the mother of Chimaera who breathed raging fire, a creature fearful, great, swift-footed and strong, who had three heads, one of a grim-eyed lion; in her hinderpart, a dragon; and in her middle, a goat, breathing forth a fearful blast of blazing fire. Her did Pegasus and noble Bellerophon slay; but Echidna was subject in love to Orthus and brought forth the deadly Sphinx which destroyed the Cadmeans, and the Nemean lion, which Hera, the good wife of Zeus, brought up and made to haunt the hills of Nemea, a plague to men. There he preyed upon the tribes of her own people and had power over Tretus of Nemea and Apesas: yet the strength of stout Heracles overcame him.

Monsters crawl inside the fogged minds of iconoclasts. But the urge to tear down statues and raise a bare stake in their stead is predicated on the need for struggle within the world of generation. Struggle raises worthy souls up, where they can help others escape. All souls can choose how to direct their will, and the play needs antagonists. Without some force pushing against the protagonist, there is no action on the stage, and a play is action (δράμα). The long-established trope of comparing human life to theatre, most efficiently employed in a philosophical context by Plotinus, is ever fruitful, never failing. And so iconoclasts must make the choice to play the part of the antagonist. The gods are good, and so the choice, iconoclast, is all yours.

Smash the idols, tear down the art beautifying the walls, swaddle all the pretty ladies head to toe in black, replace the love for beauty made manifest within the world in a myriad forms through the Titanic exsanguination of the Most High Dionysus brought beatifically low in exchange for the love of a false and earthy saviour never to come, turn religion into a low pedantic following of empty meaningless rules, bleed out the animals you eat so that their suffering delights the evil demon who burns with flame of darkness visible inside the dried womb of Mount Horeb, be a hateful clot of twisted dry resentment cut off from love of beautiful things, and lo, in the mirror you see now an iconoclast.

I saw a masterful painting. A saw a pretty lass with thighs as white as milk. I saw an insect land on a flower and paint a picture of serene fecundity. Through these signs I beheld the goodness of the world and the providential outpouring of love that births and maintains it. You, iconoclast, saw the same things and curled in a ball of hateful resentment. You will smash no idols, leftist, Protestant, Haredi, Mussulman, whoever you may be. We will instead smash your skull and grow beautiful things in idolatrous gardens from your miserable blood.

The Bible clearly misunderstands idolatry. It's authors thought that Pagans believed the idols were gods. Pagans historically understood the idols to be representations of the Gods.